Reinforcement learning with Python. Part 1

Hi there, this is the first part on reinforcement learning series. In this article I will try to explain some basic concepts using simple problem and in the next one we will implement a primitive algorithm to solve that in Python. Along the way we will create a complete solution for the real world problem using reinforcement learning techniques. Let’s get started!

Journey begins

Suppose we want to travel from Los Angeles to Last Vegas. We have a car with a tank’s volume of 60L. Along the road we have 10 gas stations which are located equally far from each other. Our driver is an agent - someone who makes decisions of what to do. He has a plenty of actions to choose from. For example at each gas station we are able to fill a tank with 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 or 60 (full tank) liters of fuel as long as there is available free volume within it. Moreover we can travel 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 or 60 km as long as there is available fuel in a tank (for simplicity sake assume 1L per km consumption). Our driver might get tired so we have one extra idle action - just staying at a gas station not moving anywhere and not replenishing a tank (probably just having some coffee). In total we have 7 actions available - that’s our action space. As you can see we have discrete action space. In other words we cannot move 15 or 21.5 kilometers - just stick with predefined values above. There are algorithms that works with continuous action space and we will have an eye on them later too. Let’s have small pause and check out the car we’ll be driving for the next couple of articles.

* this should be Tesla Model 3 but it doesn’t have a gas tank

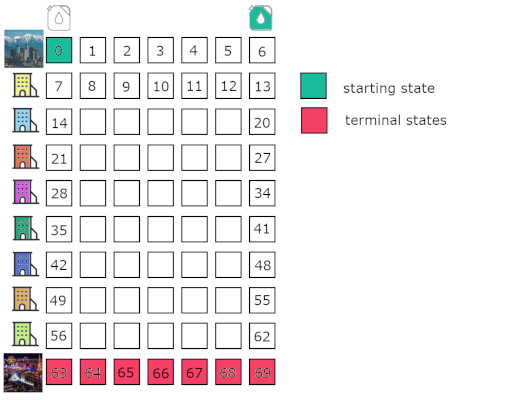

During our trip we will go through different cities (gas stations). That’s our environment - a tiny world where our agent learns and acts. We are able to visit each of those and we can describe ourselves as being in a city with a tank filled by some amount. That’s when the notion of a state comes in. State is a representation of current environment and most of the time we are only able to partially experience it’s internals by our observation. For this simple example those are indistinguishable, so let’s not dive too deep and think about it as of information we can retrieve at any time during the trip. In our case we can describe it as a (city, tank volume) pair and represent as a table.

We always start our trip from LA having an empty tank. That corresponds to (0, 0) cell in a table. Our trip ends in a last row (we may end up having some extra fuel in a tank when reaching destination point). Each column in a table corresponds to a current amount of fuel we have. Each row corresponds to a city we are currently passing through. We can represent our state space (all possible states agent can be in) with a simple 70-items list and each state can be represented as a number 0-69. From the state given we can easily figure out which city we are in and how much fuel do we have at the moment. Let’s demonstrate that with a code

1 | from typing import Tuple |

We have two helper functions which will convert our state to (city, tank volume) pair and back. Check that output of these functions corresponds to cells in our table. Being in a first yellow city with a full tank should give us 13 as a state

1 | to_state(1, 60) |

And being in state 64 means we have reached Las Vegas and still have 10L left.

1 | from_state(64) |

Our agent can learn only by interacting with the environment. In order to do that we have to drive not only once but a a lot of times the same route from LA to Sin City. Each trip might be totally different from previous one (driver may stop at different gas stations or may rest more than usual) and it’s called an episode. Each episode begins from starting state (0 in our case) and ends in special terminal state (when we have reached Las Vegas). But how do we learn during an episode?

Rewards

We begin by defining all the actions available to the agent. As usually they are easily represented by a simple list of integers.

1 | ACTIONS = [ |

The idea of the reinforcement learning is that some actions are better than others in certain states. Agent should learn how to behave optimally (in the best way possible) in each state in order to maximize its reward. It gets positive rewards when doing right/good actions and negative rewards when doing something wrong (bad actions). At each time step agent receives a reward from the environment for an action being performed. Total amount of rewards collected through an episode is called a return and the goal of an agent is to maximize the return. That’s why it’s important to properly define rewarding mechanism as it will be an intrinsic motivator for the agent to do right things.

In our environment an agent will receive negative reward of -1 at each time step. That’s reward equivalent of saying go from one place to another in shortest time. Without such a punishment our agent might decide to just stuck in one city drinking coffee and having some fun. When reaching the destination point it will get a positive reward of +20.

What should driver do in order to get maximal total reward? Intuitively we understand that we need to spend less time on gas stations and more time driving (e.g. always filling the whole tank and moving until it’s empty). But how does driver know what to do in a certain situation? The answer is by following a certain policy. In simple words policy is a mapping between states and actions. Think of it as a driver’s handbook/guide showing what to do in a city when you have read tank’s indicators. We can achieve our main goal of maximizing return by finding such a policy that will dictate best actions for any given state (kinda cheatsheet for our simple game). Let’s assume that we’ve got such a handbook from another driver that drives this route from time to time. How do we know this guide is good and whether it’s good enough for us?

Policy evaluation

In case we have existing policy we could do a rollout, just an episode for the policy given. Agent will follow recommendations from the policy and will get some return in the end. We need to implement step function and call it again and again until the end of episode.

1 | class Environment(object): |

In the code above you can see _max_steps variable introduced. That was done to add a constraint on the episode length. If agent will stuck in some city doing nothing we won’t wait forever and hope something changes. This limitation will allow an episode to eventually terminate even if the agent did not reach the termination state by himself. Also you might notice reset method which sets the environment to its initial state. As I mentioned before we will need to run a dozen of episodes and therefore we need to make sure that we do not start from the middle of the route at the beginning of a rollout.

The main method is implemented below and follows our logic of -1/+20 rewards. It makes some manipulations with an action value in order to get proper new state. Note that we are not doing any extra sanity check here and assuming that action passed is valid.

1 | def step(self, action: int) -> Tuple[int, int]: |

From this point we are ready for the whole trip at the end of which we will receive total “points” collected.

1 | def rollout(self, policy): |

At each step we are asking an agent for its decision (an action produced by the policy) and receiving a reward and a next state from the environment. We do that until episode terminates by reaching the destination or exceeding our steps constraint.

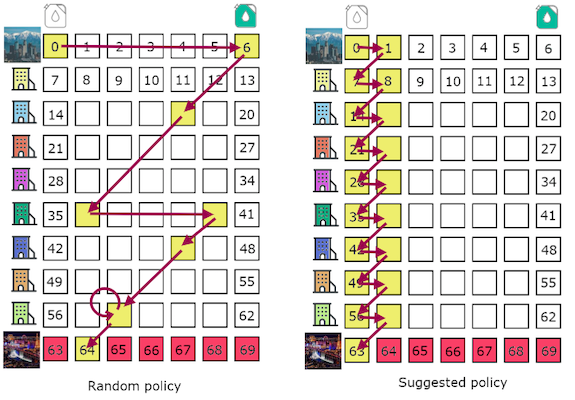

We can measure the results of the rollout and a result produced by another policy and in such way compare them. A good place to start here is always by providing some baseline for the return (some relative value we can compare later to). A random policy is usually used for that. Basically in each state driver will make its decisions by throwing a dice roll ([1] [2]) and choosing an action based on that. Here’s an implementation for the random policy.

1 | MAX_TANK_VOLUME = 60 |

As you already might have noticed some actions are not available in some states. For example we cannot go from state 0 to state 7 as we don’t have a fuel for that. We still can act with any of 0-60 though. To handle this issue policy should pick only an action which is available (based on observation). Environment on the other side should either give some large negative reward or simply not change its state (in our example we already have -1 reward for each time step, so that will do a job). After evaluating our policy we can compare that to random one and if it’s better we can set it as our new baseline and continue a process of finding the best one. Suppose that driver has been told to fill a tank with 10L in each city and then go to the next city (i. e. visit each city). We can write that as a code like this

1 | class SuggestedPolicy(object): |

You can think of it as of the big dictionary (as I mentioned policy is just a mapping) which looks like the following (when being in the first column in our table we fill a tank and for the second column we move by 10km)

1 | policy = { |

To make our policy support indexing as a dictionary we need to add one magic method

1 | def __getitem__(self, observation): |

Now we are ready to evaluate our both policies and see which one shows better results

1 | def evaluate(policy, num_episodes=1) -> float: |

As you can see we have extra num_episodes parameter. This one is needed for a valid evaluation. Due to randomness involved in our RandomPolicy we might obtain totally different results within different runs, so we just average those to have a better picture. On the other hand SuggestedPolicy will always produce the same result no matter how many episodes are played. We call such a policy a deterministic one because it gives the same output for a given state every time. Stochastic policy is an opposite one and it returns an action for the state based on some distribution (e.g. half of a time doing one action and half of a time another one). Below the result for the evaluation is presented (you may have different value for a random policy)

1 | random_policy = RandomPolicy() |

Now we know that following our colleague’s handbook we can do a better job that spontaneously selecting an action every time. Let’s have another trip with random policy and visualize it to better understand what’s going on.

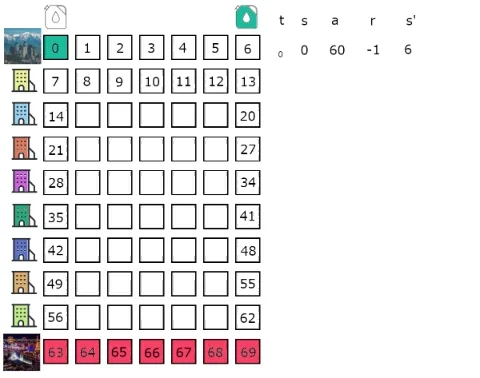

As you can see this time random policy produced even better result and that means we are still far from ideal. t parameter on the right represents our current time step (remember we have a constraint of 20 time steps); s corresponds to a current state and s' is our new state after performing action a and receiving reward r for it. Only on step with index 7 we receive a positive reward for accomplishing a goal and -1 for any other step. Note that on step 6 agent decided to stay in light green city wasting time and therefore just obtaining a negative reward for that.

When comparing sequences of cells on the table produced by a policy we might see them creating some kind of a path. We call that path trajectory and usually it’s represented by a list of (s, a, r, s') tuples.

In our case better policy will lead to shorter trajectory, so we’ll reach our destination faster.

That’s pretty much it! We’ve managed to finish our trip and now we know at the end of it whether our route was good or bad based on a reward feedback provided.

Summary

In this article we have described main terminology in reinforcement learning domain. I hope that was easy to grasp because of simple example and analogies given. In the next article we will talk about value function, action-value function, value iteration and policy iteration.

Let me know in the comments how this post can be improved and what topic you want to read about in next RL-related posts. See you soon.