TicTacToe game in Python

Intro

Computer games are a lot of fun! They are even better when written by yourself.

Creating your own game gives you a wonderful journey of learning complex concepts in a playful manner. If you’ve ever wanted to develop your own game, then it’s a perfect place to begin with.

By the end of the article, you’ll be able to:

- Create Tic Tac Toe Python game from a scratch

- Create extensible applications which are easy to refactor

- Draw graphical inteface for the game in a console

- Create another GUI frontend for the game

- Implement your own logic for the computer to play with human

This article assumes you have an understanding of lists, sets, and enums.

A basic understanding of object-oriented Python is helpful as well. Python 3.8 is recommended and used throughout this article.

NOTE: You can get all of the code in this article to follow along. Source code for the Tic Tac Toe Python game on Github

Python Tic Tac Toe Game

The rules of the game are pretty simple: two players Xs and Os are placing their marks on a 3 by 3 grid. In order to win the game, a player must fill a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal row with his symbol. In case no one succeeds to make a row of three a game is declared a draw. On the video you’ve seen first player managed to have three Xs on the diagonal and thus win the game.

Imagine being able to create such a game and play with your friend or with a computer opponent. Sounds pretty exiting, right? Let’s move ahead and get your hands dirty by wrinting some code.

Structure of the application

Planning is the most important thing for every project. Having clear picture in mind allows you to write your code faster, make less errors and avoid stagnation. That’s why you will go through the process of describing basic building blocks for the game, then envision complete architecture for the application and glue everything together by actually writing some code.

Setting up the board

Let’s start by defining a single cell of a board which can hold either of three states. Initially it’s an empty cell and it might also be an X or an O.

1 | from enum import Enum # Python 3.4+ |

On the example above you can see enumeration which is a set of members bound to unique, constant values. enum is always a great choice when you need to group a bunch of constant values together as it allows to be iterated over, compare its members, and guarantee uniqueness if needed.

Now you want to store a whole board and the easiest way to represent such a table in Python is to use list of lists. Inner lists correspond to rows of the board and outer list is just the container for them.

1 | board = [ |

Game board is empty from the start, so you provide Cell.EMPTY value for each of the cells within it as in the code above.

At this point, when the basic data structures for our game are known, you can start thinking about the formation which will hold these building blocks.

Game architecture overview

It’s always good to ponder on application design before writing any code. This kind of approach allows you to clearly understand what components of the application you’ll be working on, spot and eliminate possible flaws. Program created in such a way is easy to refactor thus you’ll spend much less time writing and debugging a code.

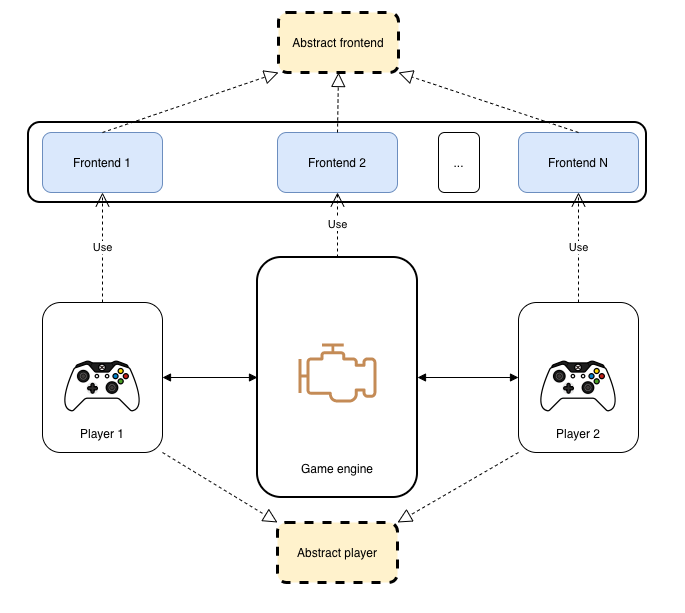

Take a look at the diagram below

In the center of it you can see a core of our game - this engine contains all the logic, process inputs and interactions with a user. On the both sides you can see a player that is bidirectionally connected to the game. On each turn player needs to receive an information about current game state and make a decision for the next action based on that. As you can see players derive from shared abstract class which means that you are able to create variety of custom players with different underlying logic as long as they conform to the interface. The same idea is behind abstract frontend: game and player are completely isolated from I/O details and you can plug any graphical user interface you want by writing an extra class for the new frontend.

NOTE: You might notice that this design generalizes really well, moreover this architecture can be applied to any turn-based two players game.

With this flexible and easy to extend blueprint you can start developing a game using top-down approach. Simply saying you should have shallow overview for the future application and then you fill the gaps by writing a code from high level definitions to actual implementations.

Creating Python package for the Tic Tac Toe game

As mentioned before skeleton for the application should be your starting point. Create a directory named tictactoe and three Python modules called io.py, game.py, and player.py.

1 | tictactoe |

Each of those files correspond to the layers on the digram: io.py will provide an abstract class for the frontends and their implementations, game.py will contain all the logic for the game engine, and player.py keeps code related to interactions with a player, either with real human or the computer bot. There are also two special files with double underscores in their names. __init__.py tells Python that all the modules within this directory belongs to the same package. __main__.py gives directives of how to run this package, so you can think of it as of an entrypoint for the game. To learn more about packages refer to this tutorial.

Next step is to create virtual environment for the application. It’s a good practice to have separate isolated environment per each project you’re working on. Command below creates and makes active virtual environment using Python’s native venv module

1 | $ python3 -m venv tictactoe # Python 3.3+ |

I personally prefer pyenv, so here’s an equivalent example of creating virtual environment using this nice tool

1 | $ pyenv virtualenv 3.8.1 tictactoe |

You are finally ready to get your hands dirty and start writing the most interesting part of any game - it’s engine!

Implementing game logic

In object oriented world each entity should be defined as a class, so you do exactly the same and create Game class to represent our Tic Tac Toe Python game.

1 | class Game(object): |

To start a game you need a board and two players, so let’s update __init__ method to include these fields. There is an extra is_x_turn boolean field keeping track of alternating turns between players.

1 | def __init__(self, x_player=None, o_player=None): |

The rest of the methods are not implemented at this point and they are marked with special keyword pass meaning they will be written later.

Game loop

A central point of the class is play method which defines a flow for the game

1 | def play(self): |

It prints initial state of the board and enters the while loop which keeps running until a game is over. It also checks for the active player and obtains a turn either from x_player or from o_player based on is_x_turn flag. Then it executes a turn by placing a given piece within a chosen index provided by player. As a last step it prints the whole board to show you current game progress. Finally outside of the loop when the game is finished there is a greeting for the winner if any or draw announcement.

Checking for game over

One critical part of the game is to check game over condition. After each turn you need to know whether there is a row, a column, or a diagonal containing specifically one symbol. Python’s set guaruantees uniqueness of elements it contains, so if all the elements added to it are equal you’ll end up having an exactly one item within it. Don’t forget to also add a condition which checks that unique element you’ve found is not an empty cell as having all equal empty values in a row doesn’t mean the game is over.

1 | # check rows |

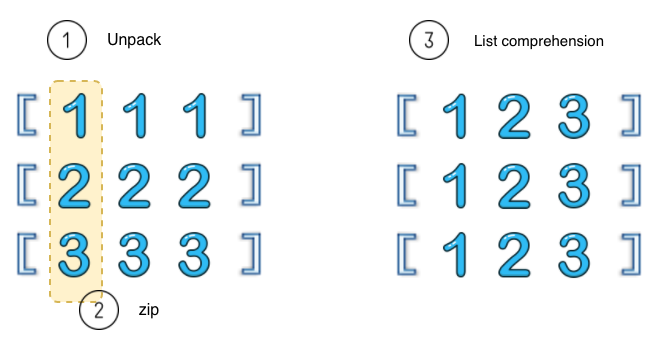

Next stop is a columns check and the logic is pretty much the same here. The only issue is that you cannot easily retrive all the columns for our board, so we need to apply tricky transformation using zip function

Look at the picture above to see how this transformation happens.

- Inner lists are being extracted as individual variables corresponding to rows.

zipfunction takes corresponding elements of those lists and group them together.- Unpacking and list comprehension is used one more time to generate new outer list which now contains inner lists with columns data.

Technical detail: This operation is equivalent to matrix transposing and you can simpy use

transposemethod when working with NumPy library

The code for the columns check look almost the same but instead of the self.board there is a rotated version of it.

1 | # check columns |

In case you’re not familiar with this weird-looking asterisk operator check out this PEP.

When both or the checks above fail you need to take a look at the diagonals. As usually set is responsible to track tokens on the line examined

1 | # check diagonals |

Last check for the size of sets and you can sign-off that the game should be still going if no criteria apply.

1 | if len(major_diagonal) == 1 and self.board[0][0] != Cell.EMPTY: |

Let’s put everything together into one is_game_over method.

1 | # game.py |

Code from the checks above will go into the _check_winner helper function, but you’ll need extra one called _check_draw to meet last request: if no winner is found the game should be terminated when no empty squares left.

1 | def _check_draw(self) -> bool: # Python 3.5 |

Essentially that maps to code that goes over each cell row by row and inspects its value. If any cell is empty then at least one move is left, so a game can not be declared as completed.

Although you can simply compare cells elementwise but note how current code is easy to generalize: it will check rows, columns and diagonals for any table provided as long as rows count is equal to columns count.

Creating an interface for a player

You’ve already seen play method which tries to obtain a move from both players and that move should be a number pointing at specific cell. In order to do that you need to define an abstract class which basically means it’s a boilerplate for other classes. You cannot create an instance of this class and only when some subclass implements all the methods required it can be instantiated. To guarantee all these constraints Python provides special ABC class to inherit from and abstractmethod decorator to mark methods as required to be implemented in child classes.

1 | # player.py |

The only mandatory method is get_turn which will retrieve from players decisions made. Another property which seems like excessive here is a frontend. You’ll see why it’s needed later, so currently a default None value has been assigned to it.

Now when it’s clear how you can retrieve a cell number from a player you can complete missing make_turn function.

1 | # game.py |

Here modular arithmetic is used to calculate row and column index for the board where a piece should be placed. One nice advantage of this code is generalization for any board size. It will work for any NxN board without any modifications required. Then flag is switched to opposite state meaning the game will ask another player to move. That’s how alternating turns are performed.

Playing with a computer

The simplest way to implement first artificial opponent is to create dummy random player. It will randomly choose an empty cell without any other considerations. Update your code with a new class for a player called RandomPlayer and make sure it provides an implementation for the get_turn method.

1 | # player.py |

One peculiarity of this player is the ability to generate new names for each player instance. As with move choices it does that in a random manner by taking eight characters from an alphabet. Above you can see string concatenation of the chars from a list comprehension. Feel free to update the length for the name or select from a list of predefined authentic names.

Moving forward to the logic for the function. There is a loop over the board checking each cell and adding indexes for them into the list to select from. You should be already familiar with a formula to calculate index from row and column number, so here is just an inverted version of it.

1 | def get_turn(self, board): |

Each empty cell index is added to the list and random module is used to select one of those.

Now you are going to create both players alongside a game instance and let them play with each other. For that you need to update an entrypoint __main__.py file with the following content

1 | # __main__.py |

To launch the game for the first time you need to invoke tictatoe module with Python interpreter using -m flag. Note that command below should be executed from parent directory which contains tictactoe folder.

1 | $ python -m tictactoe |

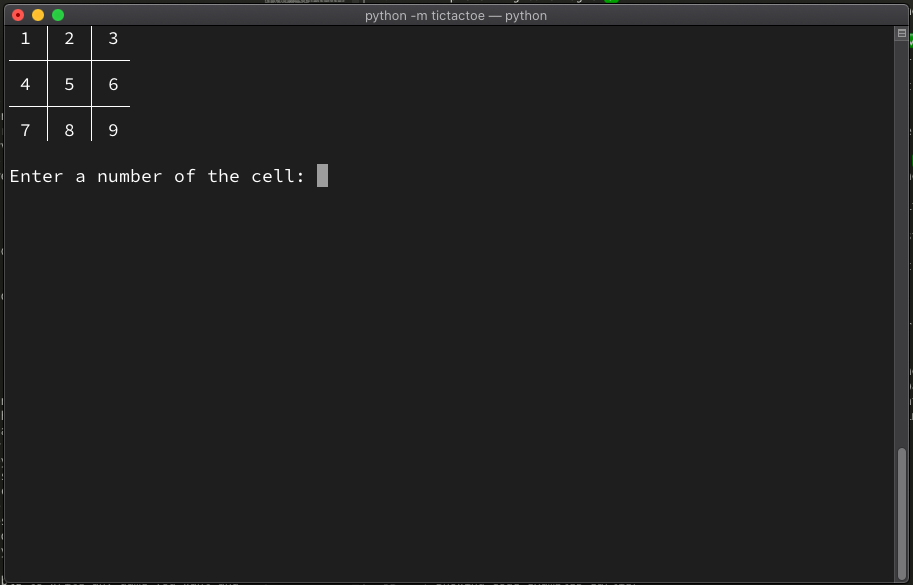

Seems like game exited successfully but you can’t see what actually happened. You obviously need some way of drawing a board state after each turn to track game’s progress.

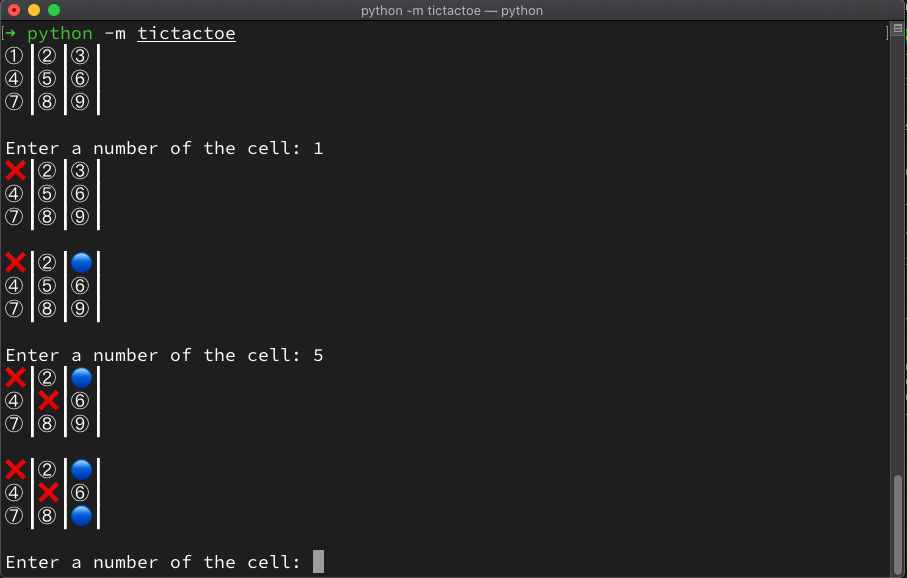

Implementing GUI frontend

Now it’s time to open the curtain in front of our code and visualize underlying game mechanics. To keep things simple you will be using regular systems console and print everything into the shell. Graphics will be character-based and Unicode symbols will be used to create a bit prettier look. As usually let’s think about a big picture first before diving into implementation details.

Defining abstract frontend

Requirements for the input-output interface are pretty straightforward:

- It should be able to display a board provided.

- It should print a message when the game ends.

- It should retrieve an information about move decision from a user.

1 | class IOFrontend(ABC): |

For each of the items in the list you have a corresponding abstract method declared. Frontend is completely separate entity which does not rely on any game internals. As long as you invoke its method with proper arguments it will handle interactions with a user for any game written. On the other hand it follows single responsibility principle which makes it independent from the rest of the application, so you can easily plug new one without affecting any other components of the program.

Drawing

Having an interface in place you can create a very first implementation of it. Begin by defining a class which inherits from IOFrontend and overrides all the methods required.

1 | # io.py |

placeholder property will be used to display hints on an empty cells, so you will know on which exact cell to place your mark. To query an actual choice input built-in function is used which simply reads everything typed on the keyboard. print_winner method when given a name declares it as a winner, otherwise a draw announcement is made.

1 | if name is None: |

To print the board itself you need to iterate over the board and print each row line by line. You check each cell and display a corresponding mark if occupied and for empty cell you show a placeholder for a vacant place. To calculate a number for a cell modular arithmetics is used once again. It’s a simple formula i * len(row) + j which takes current row and current column and gives an equivalent correspondence represented as a single number.

1 | for i, row in enumerate(board): |

Above you can see complete implementation of print_board method. Extra calls to print function without agruments are used to output new lines for cleaner look. Having that in place you can finally delegate drawing responsibilities to the frontend.

1 | # game.py |

At this point all of the stub methods are implemented and you have finished writing Game engine. You are excited to see where all of this going, aren’t you? Just invoke the module one more time with

1 | $ python -m tictactoe |

and watch two random computer players trying to defeat each other. Final step is to replace our random players and to allow you for the first time to actually play the game. In order to do that you will need another implementation of the player which interacts with real user.

1 | # player.py |

For simplicitly any kind of validation is omitted here, but ideally you should check whether an input is a number, whether given number within a range, and whether a cell on the board is indeed empty. That’s another reason why board parameter is present within function definition. Plug ConsolePlayer into the game by one small modification

1 | # __main__.py |

You can also replace x_player parameter with o_player if you want to play for the Os team and even create a two-humans game. Start by creating another instance for a new player and pass both of them to the game constructor.

1 | # __main__.py |

Try it with your friend, play for both sides, or just oversee random battles.

You should be able to see how easy is to modify game’s behaviour due to proper structure of the application and how little changes it requires. To prove this statement one more time you are going to implement another frontend and redraw a look for the game.

Alternative frontend

You’ve made a good job putting everything together, so . There are two extra libraries which can help you adjusting overall appearance, namely click and terminal tables. First one provides an ability to play around with colors and clearing the screen between moves, so only the current state of the board is visible at any given moment. Second library draws simple tables in a console and handles evrything related to alignment and borders. Install them within virtual environment using pip executable.

1 | $ pip install click |

You are ready to import these libraries and sketch a class for the new frontend. Logic for printing winner and handling input is exactly the same, the only thing you add here is colorization for the background when printing a text.

1 | # io.py |

The same applies to the print_board method - no major differences besides clearing the screen before drawing the board and making sure all the data is printed within a nice grid.

1 | # io.py |

In order to print game board as a table you need to prepare the data for it first. There is an extra list called table_data which contains the text for each cell groupped by rows. Then you create an instance for the SingleTable and remove outer borders while preserving lines inside. That makes an exact look for the Tic Tac Toe board as you used to see on a paper. Just two lines to hook up table-based frontend to our code and you are ready to play again.

1 | # __main__.py |

If everything is done properly you should be able to see this wonderful small board on your screen the same way as below

Conclusion

Every journey comes to an end, but that doesn’t mean you have to stop here. There are a lot of possible improvements you might bring into the game. In case you are interested in developing nice user interface you can check PyGame framework or become familiar with PyQt. If you want to extend a game with some new feature you can begin with storing a statistics for the game, for example number of wins, loses, and total games played. You can either store everything in a file on the disk or connect your application to the real database. As the last suggestion I’d like to point you to the minimax algorithm with the help of which you can create a perfect computer player for the game impossible to beat.

With a knowledge gained in this article you’ll be able to write any game you want and continue this exciting adventure of game development. Just keep in mind one thing: patterns in programming are always the same, learning them once well will pay off handsomely on the hundreds of applications.

Take care!